Alondra De la Parra and the art of controlled ecstasy

Fervent applause for Mexican conductor Alondra de la Parra, violist Antoine Tamestit and the Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie Bremen at the Hamburg Elbphilharmonie

By Marcus Stäbler

And yet it moves, the world of classical music: a female principal violin, a female conductor on the podium, and, on the music stands, the score of a female composer. When a top orchestra such as the Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie Bremen opens its concert at the Hamburg Elbphilharmonie with that kind of combination, it is sending a clear signal.

It is a signal that overdue changes in society have finally also reached concert halls, in the hopes that such opening lines by a music critic as those above may one day become superfluous. In the hopes that one day, in the male-dominated world of classical music, the most important aspect may be quality, not gender.

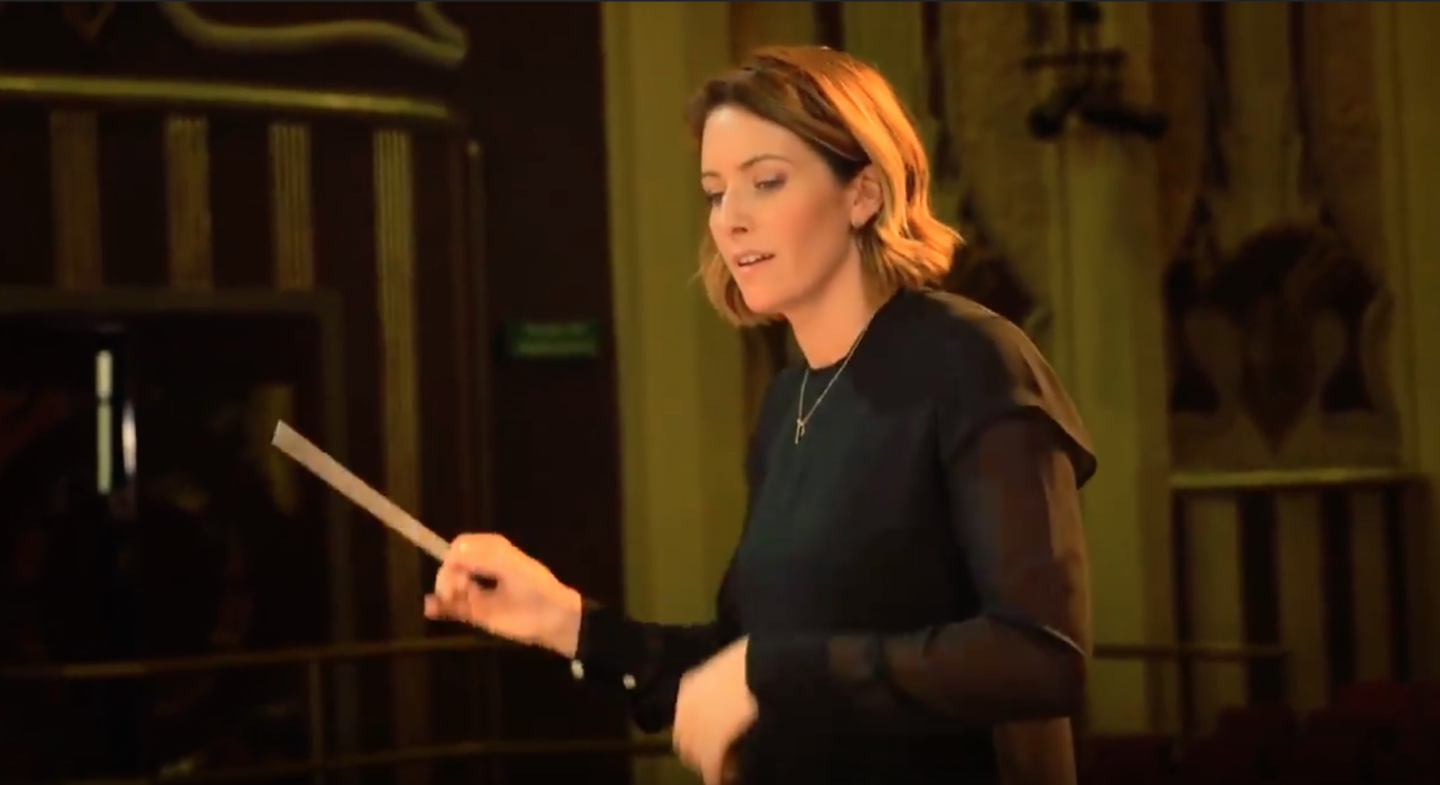

And there is much to be said here about quality. For example, the firm, rigorous body language that Alondra de la Parra used in order to guide the musicians through the scurrying and whirling music of Grazyna Bacewicz’s “Overture”. The Mexican maestra displayed a true sense of dramatic progression by handpicking that piece to open a coherent, extraordinary evening that combined music from the 20th and late 19th centuries in a programme that circled – without explicitly mentioning it – around the motto of “colors”.

The viola concerto by Bela Bartok from 1945 – one of his last pieces, written in exile and only left behind in sketches – is initially dominated by hushed, subdued tones and low, dark registers, fully and expressively highlighted by violist Antoine Tamestit with his warm sound. Only in the final movement, Allegro vivace, does Bartók finally bring the down-to-earth, occasionally rough, dancelike character of Hungarian music to the forefront, letting the soloist’s fingers race up and down upon the strings. The composer interlocks the solo part and the tutti in a high-speed battle of rhythmic exchanges for which one clearly needs a highly focused ensemble such as the Kammerphilharmonie and a soloist of the likes of Tamestit, who performs even the most demanding passages with a smile full of satisfaction – as virtuosity seems to mean joyful music-making to him, not stress.

After the intermission, the programme plunged deep into the sleepy sensuality of French Impressionism with Debussy’s “L’après-midi d’un faune”. The orchestra formed a soft bed of rustling strings and pearly harp glissandi to highlight its woodwind section’s luxuriously high standard, once more revealing an extremely refined culture of soft dynamic nuance under the baton of Alondra de la Parra. Only a few orchestras are capable of bringing out the full potential of a velvet paw pianissimo in a manner as thrilling as the Kammerphilharmonie.

Igor Stravinsky’s “Firebird Suite” likewise profited from the finely nuanced dynamics with which Alondra de la Parra shed light on its rich variety of colors, thereby revealing a direct link between Debussy and Stravinsky – except, of course, that the Russian composer traces the outlines of orchestral color with thoroughly different contours. Whereas Debussy tends to paint flowing transitions, Stravinsky prefers angular edges and glaring contrasts – particularly toward the end of the Firebird Suite, where the Mexican conductor’s explosive gestures triggered a series of razor-sharp attacks from the brass and percussion sections: violent bursts of energy for the finale of a concert that thrilled the Elbphilharmonie audience with the magic of orchestral color and the art of controlled ecstasy.